Planning a forest inventory

Large parts of AWF-Wiki are devoted to sampling and plot design techniques and the impression could arise that forest inventory is nothing else than applied statistics. While applied sampling is a crucial part in forest inventory, it should also become clear, that forest inventory is but one component in more general planning processes.

Also, forest inventories are projects that require project planning like any other project. In fact, proper and careful planning is essential to a successful forest inventory exercise. As technology advances, many situations change over years as do details of planning.

A most important aspect of a forest inventory is that there must be an explicit information requirement that justifies the need for an inventory to be carried out. This information requirement, at the best, is written down and needs to be translated and broken down into measurable indicators and attributes. It is not sufficient to say, for example, that we need to know the “forest structure” or the “biodiversity” or the “situation of the tree resource outside the forest” or the “sustainability of forest management” – but all such topics need to be expressed in terms of lists of variables (that serve as indicators) so that they become operational for a forest inventory.

It is helpful to actively search the discussion with the decision makers or those who request the information in order to make clear and illustrate the options and limitations of a forest inventory. This is at least as important as the efficient sampling and plot design.

It is difficult for many, to imagine what the results are that a forest inventory can yield. And it is a normal situation that the most concrete requirements are formulated but in the moment that the results are published, questions such as “why didn’t you also report on this and this …?” occur. While this is normal, it should be avoided to the largest possible extent through discussions prior to implementation of the inventory. In that context it is very relevant to be able to anticipate which groups of interested parties need to be interviewed. This is usually not only the foresters but possibly also experts from other sectors that are interested in forest or landscape level information such as conservation biologists, agronomists, tourism developers etc.

Contents |

"Good" forest inventory

To our best knowledge there is no such thing like “best practice” guide for forest inventories. Probably, it does not make sense to set up such a guide because the options are so manifold and the system to be sampled so complex that it is unlikely that there is one single clearly best option. It is more probable that there are various very good options. The major point is to avoid pitfalls and errors, and that is best done by consulting with experts in forest inventory sampling and those who have local expertise and can give practical advises.

There are certainly some criteria to which a forest inventory study should be conform to and that is (as in any empirical project):

- the project should be conform to the objectives;

- it should provide adequate precision;

- it should be methodologically sound and follow statistical sampling criteria;

- it should have comprehensive and transparent reporting and documentation;

- and the major criterion (to which all the above contribute) is that there is overall credibility.

Planning procedure

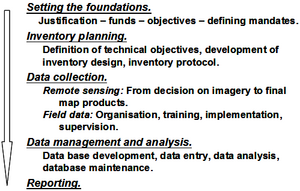

A forest inventory is a project like many other projects and general planning principles apply. Figure 1 illustrates this general procedure.

Some points are addressed in what follows:

- The objectives should be discussed in detail, and at best there should be a permanent discussion with potential users of the information to be produced also during the data collection and analysis phase. Mid-term meetings or workshops will help. The objectives determine number and type of variables to be collected. More attributes to be measured mean higher cost so that there must usually be a convincing justification as to integrate additional variables or target objects.

- A number of key features needs to be clearly and explicitly defined, although in many cases everything appears so obvious: population of interest, major attributes to be assessed, precision requirements for the major attributes and products expected such as maps (most appealing but least precise), statistics etc.;

- A forest inventory is a costly project, in particular when extensive field sampling is part of the exercise. Therefore, sufficient resources must be secured and available;

- Qualified experts, field crew leaders and teams for coordination and field work need to be found. This is not always an easy task. In what refers to field teams, thorough training is a must as is the writing of a detailed inventory manual. Only written definitions and inventory procedures guarantee that all field teams do exactly the same. Some more points about this extremely important point are discussed in the following;

- All available relevant a priori information should be compiled and evaluated such as models, maps and existing inventory reports; in this preparation phase, contact should be sought to those who know the region (forest service, forest owners association) and who possibly can give practical advises for inventory planning;

- The options should be checked whether the forest inventory can be combined with other natural resources assessments. While this appears to be a good idea, because the observation of additional variables in the field carries a relatively modest marginal cost, it is not frequently done; probably because the survey techniques and “philosophies” are so different between different disciplines;

- A decision must be made about the data sources to be used and analyzed (field data, remote sensing imagery, interviews, etc.);

- A classification system needs to be devised, for example for forest types;

- A sampling and plot design needs to be defined; in the same step, the estimation design should be defined; sampling and plot design without estimation design can result in major problems at the end of the inventory if it turns out that statistically unbiased estimation is not possible under the chosen sampling and plot design;

in that context, it is also recommendable to design a data base that is to receive the data, and to make a “pseudo”-analysis with dummy data in order to be sure that you can analyze the data as you would like it. - If remote sensing is applied, specify the classification system for image interpretation including interpretation key;

- A detailed field manual needs to be written, which defines the protocol of the inventory, form sheets need to be designed or a software developed if portable data loggers are used;

- Organizing logistics such as transportation of the field crews, availability of measurement devices, maps, etc.; if an inventory is planned that requires the field teams to stay in the forest overnight, the logistics is complex. Organization of logistics is facilitated for the coordination team if the contracts with the field teams are formulated such that they are by themselves responsible for transport, measurement devices etc. Of course, the contract must then be accordingly. This type of contract guarantees much better that cars and measurement devices are carefully treated;

- A time table needs to be set up for field work and for image interpretation.

Field teams

Training prepares the field teams in a consistent manner. It is good to train all field teams together directly prior to the inventory and to end the training with the serious tallying of a real field plot.

Further training should be given in the course of the inventory; either by convening the field teams and discussing questions and issues or by occasionally accompanying the field teams and observe there field measurement practices. The latter is a mixture of training and checking the team’s performance.

Other means of checking the quality of the team’s work is that supervising teams measure some plots again. This check cruising is usually done on about 10-15% of all plots. This is a very costly undertaking, but we must take into consideration that the data is the most important product of an inventory. All depends on the data. And that should also be known to the field teams. On the other hand, being out in the forests for weeks and months and doing field observations every day is a physically extremely demanding task. Then, it is important to keep in mind that eventually the field crews do also have it in their hands what the overall quality of the inventory results is. They are, so to say, the key persons in the inventory – but frequently also the least paid; in particular when helpers are employed that do, for example, the dbh measurements.

There are many technological options to do checks of the field teams. One may, for example, program GPS devices such that the route of the field team is recorded. Then, the inventory coordination team may later on check whether the field team was really at the sample point or not. For remote sample points, there is hardly any other chance to check.

One should try to keep the field teams motivated by making clear how important the role is that they play in the whole inventory process, by equipping them with state-of-the art technology where appropriate, by organizing in regular intervals meetings of all field teams and by visiting them frequently in the field.

Contacts should always be maintained between field crews and between coordination teams and field teams. In the ideal case, the field teams should be the ones who enter their own data into the forest inventory data base.

However, as work life is, not always do field teams perform according to the expectations of the inventory coordination. It is important to have the contracts with the field teams or the field team members such that it can be canceled if the expected quality is not delivered. Unpleasant, but some times necessary.

Field teams are organized like usual working teams: a clear assignment of responsibilities fosters smooth work flows. Usually, a clear hierarchy helps as well: there is the field crew leader, frequently a forest engineer with academic background, assisted by a technician and 2 or more helpers. The team leader takes all decisions and is responsible for the data quality. He or she records the data and coordinates and supervises the work of the others. The technician is responsible to the “more demanding” measurements that require a more intensive training such as height measurements and the usage of electronic measurement devices. Depending on the type of inventory done, the helpers are either contracted for few days or for a longer time. Their level of training and skills determines which tasks they may responsibly take on.

Forest inventory reporting

There are many formats and structures of forest inventory reports. In general, the report should contain all information required to meet the inventory’s objectives. Arrangement and wording of the report should be understandable to those who need the information provided and who will use the results.

There should be a section for the expert about all technical details that are necessary to understand if someone is interested in, for example, the sampling and plot design, while sections should also be easily accessible to the non-expert.

The structure of a typical forest inventory report may be as followed:

- Introduction including justification, legal basis (if applicable), potential, users etc.;

- data sources, sampling design, plot design and estimation design;

- organization and implementation;

- organization of data management and data analysis;

- Inventory results including totals and broken down to smaller reporting units (strata) for all relevant variables of interest;

- Areas;

- growing stock;

- forest structure, species composition;

- age classes;

- assortments;

- damages;

- dead wood;

- aspects of biodiversity like forest edge lengths;

- road infrastructure;

- technical discussion of results and inventory; description of problems encountered; possible comparison with earlier studies.

The inventory report should be the basis that allows the decision maker to convert the analyzed and condensed inventory data into relevant information.

A report should have (and this is no different from reports for other projects) an executive summary which states briefly the objectives, planning, implementation and a summary of results. It is important to always give precision statements (interval estimation). The report should have a clear description of the methods used, and specify the reasons for choosing this method and not another. All practical or other problems should be discussed as no forest inventory went perfect and as planned. Field manual and form sheets should be included into the reporting documents and maps can be provided whenever possible.

Acknowledgement is also a very important aspect.

Other information such as time consumption for different planning and implementation steps can be included (or even budget). Overall organization of the exercise, training measures and composition of field crews can be described.

Of course there is no specific way of writing a report and the principles stated above are some suggestions for a clear and transparent report. These suggestions are exercised depending on the need of the users. But incompleteness of the reports should be avoided as best as one could. These include:

- Background and objectives not clearly spelled out;

- models, definitions and measurements procedures not or not sufficiently specified;

- no precision statements;

- no implementation problems addressed, which are important to know in order to properly interpret the results, and which are interesting to know for future inventory planning;

- no information on time consumption, which is relevant mainly for future inventory planning.

Source of errors

Forest inventory is usually a complex project where often many people are involved in different steps during the process. Errors cannot be completely avoided but should be reduced to the minimum possible. It is certainly wrong “to believe” in the results of a sample based study, but one needs to know how to make a proper interpretation of the results and their associated sources of error and uncertainty.

There are various types of errors that occur in forest inventories and but they can be categorized into two classes: systematic errors and random errors:

- Systematic errors are committed when the error is systematically distributed over the population such as measurement errors due to ill calibrated devices. Systematic errors have always either the same absolute, relative size or at least the same direction.

- Random errors vary in size and usually follow a statistical distribution (the normal distribution, if we deal with a metric variable). Measurement errors that are not due to ill calibrated devices, wrong usage or misunderstandings of definitions belong to the class of random errors and occur with any measurement, be it metric variables such as height, categorical variables such as stem quality classes and plot establishment such as plot size, slope correction and border trees, or nominal variables such as tree species (where the letter is frequently not referred to as measurement error but as not-identification).

Of course, the standard error due to sampling is also a type of random error.

Model errors are another class of random errors in forest inventory which are introduced through the usage of statistical models such as volume functions or height curves. The values determined from these models deviate randomly from the true values – at least if the model applies; if the model is ill-applied in a given situation, the model error may well be a systematic error.

What we usually specify in an inventory report is the standard error, i.e. the error due to sampling. All other errors are not specified and frequently not even mentioned. It is difficult to determine the size of the measurement errors for single variables: it can only be done by repeated measurements of the same objects and evaluation the variability of those results. Also, the true size of the model errors can only be determined by closely examine the models as applied to the actual data sets.

Actually, in all steps of a forest inventory there is the chance of errors to be committed:

- find plot location and establish the plot;

- identify the tree to be measured (some trees can be overlooked, or some measured twice);

- measure, observe and classify the variables of interest;

- record the measurement (writing errors or unclear writing or digitizing wrongly);

- transport and transfer to the central “data base”.

Some of the errors can immediately be identified by so-called plausibility checks – others remain undetected.

Table 1. Error budget using Norway spruce plots for Switzerland. The level of measurment error was based on control study and expert opinion (Gertner et al. 1992[2]).

Bole volume variance (\(m^3/h)^2\) Bole volume bias \((m^3/h)\) Sampling error 11.5196 (98.416%)* [11.5203]** 0.00 (0.00%) Function error

Stem analysis

Tarif function

Sub total

0.0025 (0.213%)

0.1291 (1.1033%) [0.15280]

0.1316

0.00 (0.000%)

0.00 (0.00%)

0.00Measurement error

DBH

HT

\(D_7\)

Site index

Percent slope

Subtotal

0.0000 (0.0000%)

0.0017 (0.0145%)

0.0276 (0.2361%)

0.003 (0.0028%)

0.008 (0.0066%)

0.304%

0.00 (0.000%)

0.00 (0.000%)

0.00 (0.000%)

0.00 (0.000%)

0.00 (0.000%)

0.00Classification error

Crown postition

Tarif function

Subtotal

0.0090 (0.0768%)

0.0143 (0.1225%)

0.0233

0.00 (0.000%)

0.00 (0.000%)

0.00Grand total 11.704 0.00

* Number in parentheses are the percent change of the mean square error due to that source. ** Numbers in square brackets are the variances not adjusted for nonsampling error.

There are not many studies that deal with an analysis of errors in forest inventories. Usually, we take the measured data as truth; or at least as the best available data. Gertner et al. (1992[2]) researched into the contribution of the different error sources to the total error and they called this approach the “error budget” (Table 1). They found for the example of the Swiss National Forest Inventory, that, in fact, the standard error is by far the largest contributor to the total error. That results seem to indicate – at least tentatively – that specifying only the standard error in inventory reports is justified by the fact that the standard error determines the largest share of the total error; in this case more than 98%!

References

- ↑ Kleinn, C. 2007. Lecture Notes for the Teaching Module Forest Inventory. Department of Forest Inventory and Remote Sensing. Faculty of Forest Science and Forest Ecology, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen. 164 S.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Gertner G. and M. Köhl. 1992. An Assessment of Some Nonsampling Errors in a National Survey Using an Error Budget. Forest Science 38(3): 525-538.