Volume functions

(→Modeling stem volume) |

|||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

where volume is calculated as a function of one single “composed” variable: In fact, this function is identical with the form factor approach to volume calculation, only that here the constant values <math>f</math> and <math>\frac{\pi}{4}</math> are together “hidden” in the regression coefficient <math>b_1</math>. | where volume is calculated as a function of one single “composed” variable: In fact, this function is identical with the form factor approach to volume calculation, only that here the constant values <math>f</math> and <math>\frac{\pi}{4}</math> are together “hidden” in the regression coefficient <math>b_1</math>. | ||

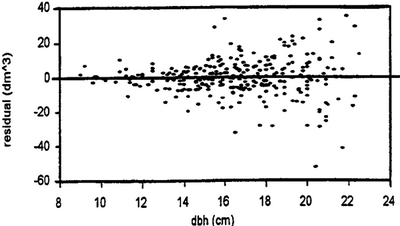

| − | [[File:2.8.4-fig39.png|right|thumb| | + | [[File:2.8.4-fig39.png|right|thumb|400px|'''Figure 2''' Residual plot of residual volume (<math>dm^3</math> as Y-axis and ''dbh'' (cm) as X-axis showing unequal variance across ''dbh'' classes (Kleinn 2007<ref name="kleinn2007">Kleinn, C. 2007. Lecture Notes for the Teaching Module Forest Inventory. Department of Forest Inventory and Remote Sensing. Faculty of Forest Science and Forest Ecology, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen. 164 S.</ref>).]] |

{|border="1" cellspacing="0" | {|border="1" cellspacing="0" | ||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

In large area forest inventories where we can not safely assume that the stem shape is relatively constant or a simple linear function of ''dbh'', it is recommendable to use a further variable that gives information about [[stem shape]], an [[upper stem diameter]]. Table 1 gives some of the common models. In the German National Forest Inventory, for example, the diameter at 7 m height is measured at the stem and accordingly processed in volume functions. In fact, not only volume is then derived but the whole [[taper curve]] is modeled from the observation of species, ''dbh'' and diameter at 7 m. | In large area forest inventories where we can not safely assume that the stem shape is relatively constant or a simple linear function of ''dbh'', it is recommendable to use a further variable that gives information about [[stem shape]], an [[upper stem diameter]]. Table 1 gives some of the common models. In the German National Forest Inventory, for example, the diameter at 7 m height is measured at the stem and accordingly processed in volume functions. In fact, not only volume is then derived but the whole [[taper curve]] is modeled from the observation of species, ''dbh'' and diameter at 7 m. | ||

| − | Figure 1 does not only show the typical curvature of a volume function, but also the fact that variability over dbh-classes is not constant over the ''dbh'' range! That means that the assumption of homoscedasticity as stipulated for linear regressions does not hold. This is even clearer illustrated when we graph the residuals over ''dbh''. Residuals are the deviations of the actual values (the volume-''dbh'' data points in Figure 1) from the predicted values (the corresponding values on the regression line). This is shown in Figure 2; it is very obvious that the range (that is, the variability) increases approximately proportional to ''dbh''. | + | Figure 1 does not only show the typical curvature of a volume function, but also the fact that variability over dbh-classes is not constant over the ''dbh'' range! That means that the assumption of homoscedasticity as stipulated for linear regressions does not hold. This is even clearer illustrated when we graph the residuals over ''dbh''. Residuals are the deviations of the actual values (the volume-''dbh'' data points in Figure 1) from the predicted values (the corresponding values on the regression line). This is shown in Figure 2; it is very obvious that the range (that is, the variability) increases approximately proportional to ''dbh''. |

| − | + | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 21:46, 1 March 2011

| sorry: |

This section is still under construction! This article was last modified on 03/1/2011. If you have comments please use the Discussion page or contribute to the article! |

Contents |

General observations

Volume functions are statistical models that describe the relationship between tree volume (dependent variable, to be predicted) with dbh, some times in combination with other variables such as tree height or an upper stem diameter. Before modeling volume as a function of one or more predictor variables, the variable “volume” needs to be defined. It is frequently defined as total stem volume from the felling cut up to a top diameter of 7 cm or 10 cm. However, volume functions may also refer to commercial volume only which is then the volume of the commercial stem parts which is again a matter of definition. Also, when working in regions with which one is not perfectly familiar, it is a good idea to verify in which height dbh is commonly measured.

Modeling stem volume

Volume functions have very typical shapes. Let’s recall the simple volume model with the form factor that reduces the cylinder volume to the true volume\[V=ghf=\frac{\pi}{4}d^2hf\,\].

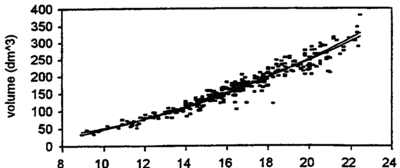

We see that dbh is the only variable that enters squared. That means that dbh has the greatest weight for volume prediction and it means also that, when volume is modeled as a function of dbh, the function must be increasing quadratically. A typical volume function is given in Figure 1. As with height curves, volume functions are given as mathematical functions that can directly be used in analysis software. In earlier times, volume tables were common, where volume could be read as a function of dbh or in a two way table as a function of dbh and height.

Various groups of volume functions are distinguished. The most simple ones are those that model volume as a function exclusively of dbh; these volume models are some times also referred to as volume tariffs. They are applied for smaller area forest inventories like stand inventories. The fact that neither height nor stem shape is explicitly included into that model means that we assume that both height and stem shape can be sufficiently well predicted also by dbh. This is approximately true, above all, for the small area forest inventories, where a major field of application for these volume tariffs exists. Table 1 gives some of these tariffs. It should be observed that, although it is only one subject-matter variable that is being included, it is not simple linear regressions as dbh does also occur as dbh² which is then a second variable in the model.

A further category of volume functions uses dbh and height as independent (predictor) variables. This adds more flexibility to the model to adjust to changing dbh-height relationships as they occur in medium size forest inventories such as forest enterprise inventories or forest management inventories. This type of volume function assumes that the stem shape can reasonably well be predicted also by dbh. Table 1 gives some of the common models. Interesting there is the model

\[v=b_1dbh^2h\,\]

where volume is calculated as a function of one single “composed” variable: In fact, this function is identical with the form factor approach to volume calculation, only that here the constant values \(f\) and \(\frac{\pi}{4}\) are together “hidden” in the regression coefficient \(b_1\).

| Table 1 Different types of models for volume functions, depending on the geographical range of application (after Zöhrer 1980[2]) | ||

| \(v=f(dbh)\,\) | \(v={b_0}+{b_1}{dbh}^2\,\) | Also called volume tarifs. |

| \(v={b_0}+b_1{dbh}+{b_2}{dbh}^2\,\) | Mainly for local studies where homogeneity of site conditions is expected, including relatively strong relationships between dbh and height and between dbh and form factor. | |

| \(v=f(dbh\mbox{, h}\,)\) | \(v=b_1{dbh}^2h\,\) \(v=v=b_0+b_1{dbh}^2{h}\,\) |

Mainly for regional forest inventories. |

| \(v=f(dbh,h,d_u)\,\) | \(v=b_0+b_1*d_u{dbh}*h\,\) | For larger area forest inventories where heterogeneous site conditions are expected. Therefore, height is included into the model to cope for variability of height curves; and an upper diameter \(d_u\) to cope for variability of form factor. |

In large area forest inventories where we can not safely assume that the stem shape is relatively constant or a simple linear function of dbh, it is recommendable to use a further variable that gives information about stem shape, an upper stem diameter. Table 1 gives some of the common models. In the German National Forest Inventory, for example, the diameter at 7 m height is measured at the stem and accordingly processed in volume functions. In fact, not only volume is then derived but the whole taper curve is modeled from the observation of species, dbh and diameter at 7 m.

Figure 1 does not only show the typical curvature of a volume function, but also the fact that variability over dbh-classes is not constant over the dbh range! That means that the assumption of homoscedasticity as stipulated for linear regressions does not hold. This is even clearer illustrated when we graph the residuals over dbh. Residuals are the deviations of the actual values (the volume-dbh data points in Figure 1) from the predicted values (the corresponding values on the regression line). This is shown in Figure 2; it is very obvious that the range (that is, the variability) increases approximately proportional to dbh.

References

- ↑ Kleinn, C. 2007. Lecture Notes for the Teaching Module Forest Inventory. Department of Forest Inventory and Remote Sensing. Faculty of Forest Science and Forest Ecology, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen. 164 S.

- ↑ Zöhrer F. 1980. Forstinventur – Ein Leitfaden für Studium und Praxis. Verlag Paul Parey. 207 S.